AAIC 2024: Early Alzheimer’s disease patients reap sustained benefits from long-term lecanemab treatment

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2024 held in Philadelphia, US, researchers presented latest findings on the use of the dual-acting, anti–amyloid beta (Aβ) protofibril antibody, lecanemab, for treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Topics covered included the paradoxical brain volume changes associated with anti-amyloid immunotherapy and the 3-year clinical efficacy results of continuous lecanemab treatment from the phase III Clarity AD study.

Paradoxical brain volume loss in anti-amyloid immunotherapy trials

A brain volume change was first observed 20 years ago in the AN1792 anti-Aβ vaccine trial, where higher anti-Aβ antibody titres correlated with more brain shrinkage. However, these antibody responders also had better cognitive outcomes compared with the placebo group, which suggested that this phenomenon was unlikely to be caused by excess neurodegeneration. [Neurology 2005;64:1563-1572]

Since then, increased brain volume reduction and ventricular enlargement have consistently been reported in several anti-amyloid immunotherapy trials. [Lancet Neurol 2024;23:1025- 1034] In the phase III Clarity AD trial of lecanemab, there was 4.1 mL excess brain volume shrinkage relative to placebo (equivalent to 0.4 percent of baseline) over the 18-month treatment period (p<0.0001). In addition, there were 0.02 mm greater reduction in cortical thickness (p<0.0001) and 1.8 mL greater increase in ventricular volume (p<0.0001). Notably, patients who received lecanemab had 0.02 mL less hippocampal volume loss (p=0.0039), indicative of a neuroprotective effect. [Bateman RJ, CTAD 2022]

Explaining the brain volume change

“There are several possible explanations for this pattern,” said Professor Nick Fox of University College London, London, UK. “It could be related to the removal of amyloid plaques and the associated inflammatory cells, or more worryingly, increased neurodegeneration or toxicity related to the release of oligomers from amyloid plaques or mediated through amyloid-related imaging abnormalities–oedema [ARIA-E], or alterations in fluid dynamics or fluid shifts.”

Associated with amyloid plaque clearance

“The excess brain volume loss is compatible with the volume occupied by amyloid plaques in AD,” Fox explained. “Amyloid plaques are space-occupying large structures. They are more than just amyloid. They are comprised of other proteins, dystrophic neurites, and associated immune/inflammatory cells, such as astrocytes and microglia. Resolution of this associated inflammatory response may also contribute to brain volume loss following plaque removal.”

An autopsy of an AD patient’s brain tissue from the Queen Square Brain Bank in London, UK, showed that 12 percent of the fusiform gyrus was occupied by amyloid plaque. [Fox N, AAIC 2024] Other post-mortem studies of AD patients found that amyloid plaques typically took up 6–8 percent of the cortex. [Ann Neurol 2008;63:204-212; Lancet Neurol 2012;11:669-678; Brain 2022;145:2161-2176] “This equates to 2–4 percent of whole-brain volume, and plaque clearance can easily account for the 0.4 percent excess brain shrinkage seen with lecanemab,” noted Fox. [J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013;72:462- 471] Even in patients with preclinical AD, where the process of amyloid accumulation takes decades, studies have shown increases in cortical thickness. [Alzheimers Dement 2021;17:618-628; Neurology 2020;94:e2026-e2036; Brain Commun 2022;4:fcac134]

Autopsy findings of AD patients treated with various immunotherapies demonstrated the extent of amyloid plaque clearance compared with untreated controls. One patient who received aducanumab for 32 months had a near absence of plaques, while another on lecanemab over an interrupted 6-year period had no diffuse plaques and only sparse neuritic plaques. [Acta Neuropathol 2022;144:143-153; Honig LS, AAIC 2022]

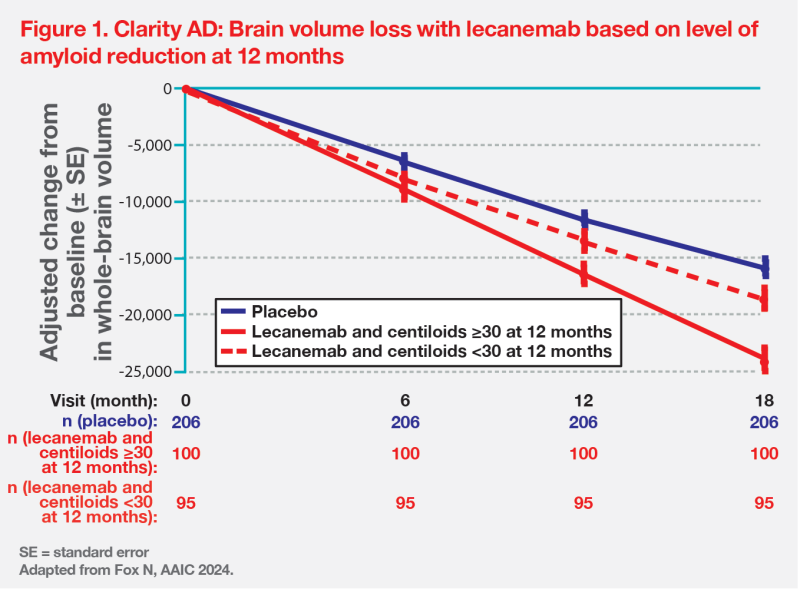

Across different anti-amyloid immunotherapy trials, the extent of excess brain volume reduction was proportional to the degree of amyloid removal. Only immunotherapies that achieved amyloid removal were associated with excess brain volume loss. [Lancet Neurol 2024;23:1025-1034] At the patient level, greater excess brain volume loss was correlated with more amyloid removal or greater baseline amyloid levels. [Fox N, AAIC 2024]

In Clarity AD, the rate of whole-brain volume loss in patients on lecanemab who cleared amyloid plaque early (amyloid PET centiloids <30 at 12 months) started to slow down to about the rate seen with placebo, whereas in those still clearing amyloid (≥30 centiloids at 12 months), shrinkage remained accelerated. (Figure 1)

Lecanemab treatment resulted in decline of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an astrocytic biomarker, which provides evidence for resolution of the inflammatory response and volume loss that follows plaque removal. [J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013;72:462-471; Bateman RJ, CTAD 2022]

No correlation with neurodegeneration or cognitive decline

In Clarity AD, lecanemab was not associated with worsening in any neurodegenerative biomarkers or clinical outcomes, suggesting that the accelerated brain volume loss observed was not harmful. [N Engl J Med 2023;388:9-21] In addition, the whole-brain volume loss correlated with better cognitive outcomes. For the same degree of brain shrinkage, there was less functional decline on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) scale and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment (ADCS-MCI-ADL) for patients on lecanemab vs placebo. [Fox N, AAIC 2024]

“Both patient- and group-level analyses support an association between this excess brain volume loss and clinical efficacy. We may be seeing a slowing of underlying neurodegeneration with the finding of less hippocampal shrinkage [on lecanemab relative to placebo]. Therefore, instead of calling this [process] paradoxical, a more appropriate term would be ‘amyloid removal–related pseudo-atrophy’ or ‘ARPA’, while we await long-term outcomes,” concluded Fox.

Lecanemab’s long-term clinical efficacy in Clarity AD

Clarity AD was a multicentre, phase III, double-blind trial that randomized 1,795 early AD patients 1:1 to receive lecanemab 10 mg/kg or placebo biweekly during an 18-month core study period. The primary endpoint was change in CDR-SB from baseline at 18 months. All patients who completed the core study were allowed to enter an open-label extension (OLE) phase and receive lecanemab 10 mg/kg biweekly for at least an additional 18 months. [N Engl J Med 2023;388:9-21; van Dyck CH, AAIC 2024]

At the end of the core study period, lecanemab demonstrated a 27 percent reduction in clinical decline as measured by CDR-SB vs placebo. [N Engl J Med 2023;388:9-21; van Dyck CH, CTAD 2022] OLE results showed a cognitive edge in participants who received continuous lecanemab treatment for 3 years (early-start group) over those who transitioned from placebo at 18 months (delayed-start group). Nonetheless, both groups did better than a matched AD neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) cohort – an observational cohort that represents the exact population of those enrolled in Clarity AD. [van Dyck CH, AAIC, 2024]

Delayed progression to next AD stage

Continuous lecanemab treatment through 36 months meaningfully delayed time to worsening on CDR-SB. Responder analysis showed that the early-start group had a 30 percent significant reduction (hazard ratio [HR], 0.70; 95 percent CI, 0.59–0.84) compared with the ADNI group in progression to the next AD stage (ie, shift in CDR-SB score representing progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia or from mild AD to moderate/severe AD). [van Dyck CH, AAIC 2024]

Long-term efficacy in very early-stage AD

Initial results from the tau PET longitudinal substudy (n=342/1,795) of Clarity AD showed that lecanemab slowed the accumulation of tau pathology in the temporal lobe regions – the area known to have the most tau PET signal in the no/low tau subgroup (standardized uptake value ratio [SUVR] <1.06), which represents a very early stage of AD. [van Dyck CH, AAIC 2024]

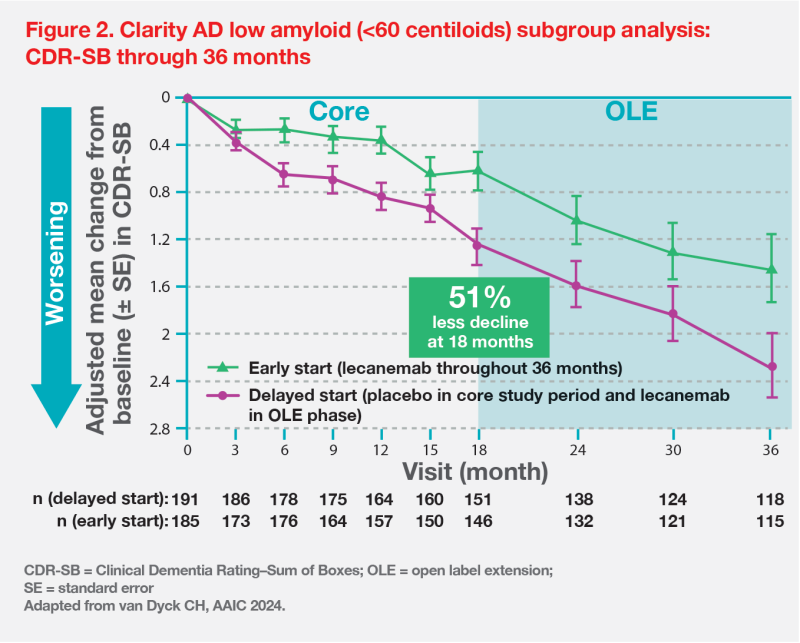

The impact of lecanemab on cognitive decline in this no/low tau population was difficult to interpret, given the small sample size (n=141/342). Hence, Professor Christopher van Dyck of Yale School of Medicine, Connecticut, US, identified very-early-stage AD patients from the full cohort by using baseline amyloid levels <60 centiloids as a proxy for low tau load.

At the end of the core study period, the subgroup of patients with low amyloid burden (<60 centiloids) treated with lecanemab showed a robust response of 51 percent less cognitive decline vs placebo, compared with the 27 percent slowing of decline seen in the overall population. “The difference between the early- and delayed-start groups persisted through the OLE period and remained significant, consistent with a disease-modifying effect,” noted van Dyck. (Figure 2)

After 3 years of continuous lecanemab treatment, 46 percent of participants in this low-amyloid population remained stable and 33 percent showed improvement in CDR-SB. Similar rates were observed in key secondary outcomes, such as the 14-item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog14: 46 and 43 percent, respectively) and ADCS-MCI-ADL (51 and 48 percent, respectively).

“These low pathology groups do very well on lecanemab, and this underscores the importance of early intervention,” pointed out van Dyck.