Aiming for clinical remission in severe asthma

The introduction of targeted biologic therapies has revolutionized the management of severe asthma, where clinical remission is now viewed as a realistic treatment goal. In an interview with MIMS Doctor, Professor Ken Ka-Pang Chan of the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, discussed updates in the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2024 Report that reflect recent research findings on clinical remission with biologic therapy. He further highlighted how tezepelumab, a first-in-class monoclonal antibody that targets thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), may help achieve this goal through its broad action on multiple downstream inflammatory pathways involved in asthma pathophysiology.

GINA 2024 updates

Clinical remission as a therapeutic endpoint

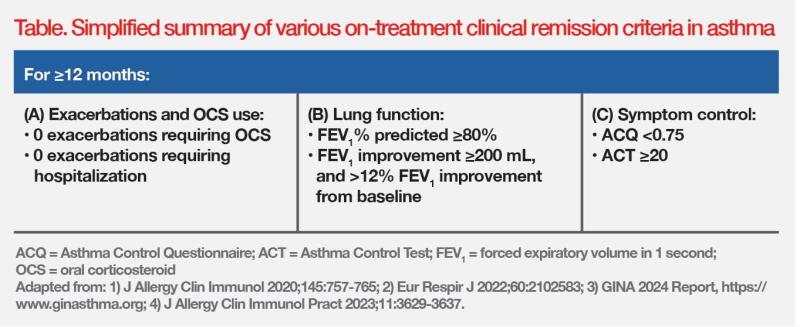

The GINA 2024 Report recognizes that the concept of on-treatment clinical remission is consistent with GINA’s long-term goal of asthma management, to achieve the best possible long-term asthma outcomes for the patient. [GINA 2024 Report, https://www.ginasthma.org] The criteria for on-treatment clinical remission include no asthma symptoms, no exacerbations, no use of oral corticosteroids (OCS), and stable or improving lung function, over a defined prolonged period. (Table) [J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145:757-765; Eur Respir J 2022;60:2102583]

“In clinical trials that evaluated biologic therapy, about 15 percent of patients with severe asthma achieved clinical remission within 12 months,” pointed out Chan. “However, achievement of on-treatment clinical remission in real-world clinical practice can be challenging, as it depends on the individual’s asthma severity, comorbidities, adherence to treatment, and access to appropriate therapies.” [Adv Ther 2022;39:2065-2084]

It is important to distinguish between severe asthma and uncontrolled asthma, which could be due to modifiable factors such as incorrect inhaler technique or poor medication adherence. [GINA 2024 Report, https://www.ginasthma.org] “Reinforcing medication compliance can sometimes improve asthma control,” said Chan. “Of note, biologic therapies are generally associated with better adherence than inhaled corticosteroids [ICS].” [Chest 2021;159:924-932]

Background therapy reduction as a treatment goal

GINA 2024 recommends stepping down therapy for severe asthma patients receiving biologics plus high-dose ICS and long-acting β-agonist (ICS-LABA) who are well controlled with stable lung function for 3–6 months. The recommendation is to gradually decrease or stop OCS first, and then consider reducing ICS-LABA dose but not completely stop ICS. [GINA 2024 Report, https://www.ginasthma.org]

This recommendation is supported by evidence from the randomized, open-label, active-controlled, phase IV SHAMAL study. Adult patients with severe eosinophilic asthma controlled on benralizumab plus high-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and anti-inflammatory reliever treatment (MART) (n=208) were randomized (3:1) to taper their high-dose ICS to a medium, low, and as-needed dose (reduction group), or continue ICS-formoterol (reference group) for 32 weeks, followed by a 16-week maintenance period. [Lancet 2024;403:271-281]

Overall, 92 percent of patients successfully reduced their high-dose ICS (15 percent to medium dose, 17 percent to low dose, and 61 percent to as-needed only) without change in asthma control. Among these patients, 96 percent maintained their reduced MART regimen through week 48, with 91 percent of patients in the treatment reduction arm remaining exacerbation-free during tapering. Clinical remission (ie, no exacerbations, <10 percent deterioration in forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], and five-item Asthma Control Questionnaire [ACQ-5] score <1.5 or ≤0.75) rates in the reduction group were 56 percent at week 32 and 54 percent at week 48. [Lancet 2024;403:271-281]

“SHAMAL provides solid evidence for safely stepping down MART without losing asthma control,” emphasized Chan. “Reduction in the use of high-dose ICS spares patients from systemic side effects such as osteoporosis, diabetes and cataracts. Additional implications include cost savings and simplified treatment regimens, which may potentially improve drug compliance.” [Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;199:1471-1477]

Some patients who stepped down to as-needed ICS-formoterol experienced decline in prebronchodilator (preBD) FEV1 and increase in fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration. [Lancet 2024;403:271-281] This prompted GINA 2024 to advise against completely stopping maintenance ICS-containing therapy in patients with severe asthma. [GINA 2024 Report, https://www.ginasthma.org]

“ICS-formoterol as MART should be continued because it provides both anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator effects, which help to maintain asthma control and prevent exacerbations. Continuing this therapy ensures that patients have a safety net in case of exposure to triggers or during periods of increased symptoms, while still benefitting from the reduced side effects of lower ICS doses,” noted Chan.

Epithelial cytokines drive asthma pathophysiology

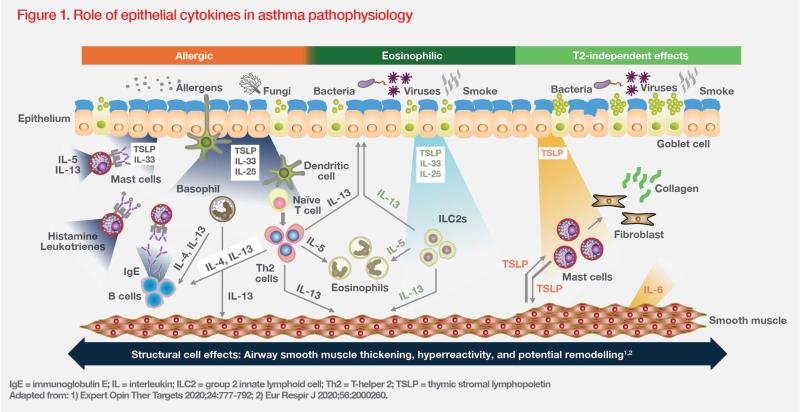

The airway epithelium plays a pivotal role in pathogenesis of asthma. Exposure to environmental triggers (eg, allergens, pathogens, pollutants) can initiate the release of epithelial cytokines, such as TSLP, interleukin (IL)- 25 and IL-33, which drive downstream inflammatory processes. (Figure 1) [Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000260]

Airway remodelling

Chronic inflammation and damage to airway epithelium result in structural changes in the large and small airways, collectively referred to as airway remodelling. Features of airway remodelling include epithelial dysfunction, goblet cell hyperplasia, thickened reticular basement membrane, subepithelial fibrosis, increased airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass and angiogenesis. These features cause narrowing and stiffening of the airways, resulting in airflow limitations and worsening of respiratory symptoms. [Eur Respir J 2024;63:2301619; J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024;153:1181-1193]

Mucus plugging

Some structural changes associated with airway remodelling, such as goblet cell hyperplasia and submucosal gland hypertrophy, can cause increased sputum production with airway narrowing, and increased airway wall thickness. These changes can ultimately result in the formation of mucus plugs, leading to severe airflow obstruction and death. [Eur Respir J 2024;63:2301619]

AHR

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) is a key clinical feature of asthma. It is defined as a predisposition to airway narrowing in response to stimuli that produce little to no effect in healthy individuals. A complex interplay between airway inflammation, airway remodelling and structural changes contributes to AHR. Importantly, ASM is considered the main cell type involved in AHR. Evidence shows that a bidirectional crosstalk between mast cells and ASM may drive AHR. [J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024;153:1181-1193; Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792]

Early remission for permanent damage prevention

“Persistent airway inflammation increases the extent of fibrosis and remodelling, which becomes progressively irreversible,” explained Chan. “Once severe asthma has developed, it may be impossible to normalize these structural changes even with aggressive treatment approaches. Therefore, achieving clinical remission in the early stages is important to prevent permanent damage, preserve lung function, and reduce exacerbations, which would ultimately improve patients’ quality of life [QoL].”

TSLP – an upstream target

TSLP is a key epithelial cytokine that mediates both type 2 (T2)–driven (allergic/nonallergic eosinophilic) and non–T2- driven (nonallergic/noneosinophilic) inflammation as well as structural changes in the airway by affecting various adaptive and innate immune cells and structural cells. It contributes to AHR, mucus overproduction and airway remodelling via its actions on the T-helper 2 (Th2) proinflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. There is also evidence that TSLP acts through Th2-independent mechanisms. (Figure 1) [Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792]

“Targeting TSLP with a monoclonal antibody, such as tezepelumab, can potentially block multiple downstream inflammatory pathways [involved in asthma pathogenesis],” explained Chan. “TSLP blockade can improve severe asthma by reducing Th2 cytokine levels, preventing structural alterations in the airways [eg, airway remodelling, mucus plugging], and decreasing AHR. It is beneficial for patients with severe asthma who have an allergic or eosinophilic component to their disease as well as those with noneosinophilic disease.” [Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792]

On-treatment clinical remission

The phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled NAVIGATOR trial demonstrated that patients with severe uncontrolled asthma in the tezepelumab group (n=528) had fewer exacerbations as well as better lung function, asthma control and health-related QoL (HRQoL) vs the placebo group (n=531) over a period of 52 weeks. [N Engl J Med 2021;384:1800-1809]

An exploratory analysis assessed on-treatment clinical remission, defined as meeting all remission components at week 52: six-item ACQ (ACQ-6) score ≤0.75, improvement from baseline in preBD FEV1 of >20 percent or preBD FEV1% predicted value of >80 percent, no OCS use, no exacerbations, healthcare professional assessment of “much improved” or “very much improved”, and patient assessment of “no symptoms” or “minimal symptoms”. This analysis demonstrated a >3-fold higher odds of achieving clinical remission with tezepelumab vs placebo (odds ratio [OR], 3.42; 95 percent confidence interval [CI], 1.93–6.05). [Eur Respir J 2022;60:2287]

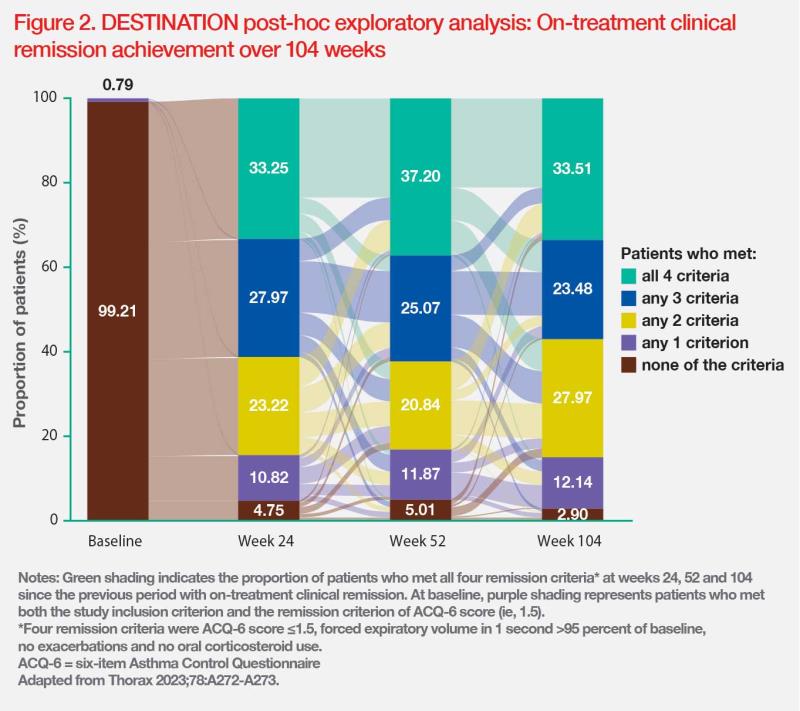

The rate of on-treatment remission after 2 years of tezepelumab treatment was evaluated in the phase III, randomized, DESTINATION long-term extension trial, which recruited patients with severe uncontrolled asthma who completed treatment in the NAVIGATOR and SOURCE studies. The criteria for clinical remission in this post-hoc analysis were ACQ-6 score ≤1.5, FEV1 >95 percent of baseline, no exacerbations and no OCS use. The analysis showed a higher clinical remission rate in the tezepelumab vs placebo group during weeks 0–52 (28.5 vs 21.9 percent; OR, 1.44; 95 percent CI, 0.95–2.19) and weeks >52–104 (33.5 vs 26.7 percent; OR, 1.44; 95 percent CI, 0.97–2.14). (Figure 2) [Lancet Respir Med 2023;11:425-438; Thorax 2023;78:A272-A273]

Reduction in mucus plugging and AHR

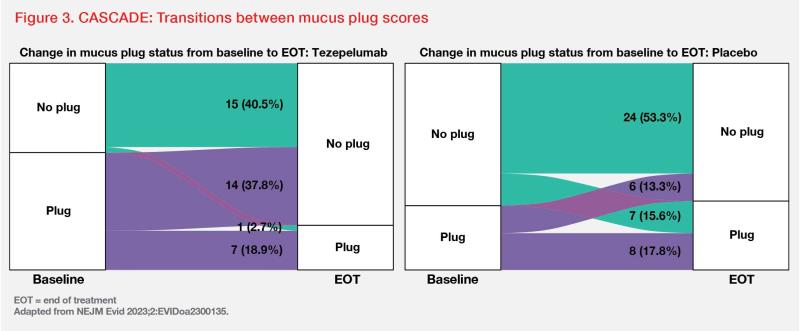

The phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled CASCADE study explored the anti-inflammatory effects of tezepelumab in 116 patients with moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. [Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1299-1312]

Changes in mucus plug scores from baseline to end of treatment (EOT) were assessed in 82 patients who completed ≥20 weeks of treatment. Tezepelumab reduced mucus plug scores vs placebo at EOT (absolute mean change from baseline, -1.7 vs 0.0), which correlated with improvements in lung function. At EOT, 37.8 vs 13.3 percent of patients in the tezepelumab vs placebo group transitioned from having ≥1 mucus plug to having none. (Figure 3) [NEJM Evid 2023;2:EVIDoa2300135] An exploratory analysis also showed that tezepelumab significantly reduced AHR to mannitol vs placebo (nominal p=0.03). [Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1299-1312]

“Reductions in AHR to mannitol and mucus plugging observed with tezepelumab contribute to clinical remission by improving airway obstruction and reducing inflammation, leading to better asthma control and potentially halting disease progression,” commented Chan.

“Tezepelumab has demonstrated efficacy in a broad spectrum of asthma phenotypes,” he noted. “Two subgroups of patients can derive particular benefit from tezepelumab. The first is patients with low eosinophilic/allergic inflammation in the airway, as tezepelumab’s efficacy is independent of baseline eosinophil levels, unlike other approved biologic therapies. The second group is patients who remain uncontrolled or nonresponsive to other biologics targeting eosinophil [or allergic] inflammation. Since tezepelumab acts further upstream in the inflammatory cascade, it has a broad impact on multiple drivers of asthma.” [Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;207:A4750; Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792]

Future of severe asthma treatment

New biologic therapies targeting different inflammatory pathways in asthma will continue to emerge in the future. Choice of treatment will be tailored to individual patients to maximize clinical benefit. “Most importantly, the treatment goal will shift from asthma control to clinical remission,” commented Chan. “Early intervention with biologics may help achieve clinical remission early in the disease course, which will halt asthma progression and reduce overall drug burden.”