Corticosteroid elimination with anti–IL-5 antibody in two patients with idiopathic HES

Case 1: OCS-dependent idiopathic HES patient with skin involvement

History, presentation and investigations

A 45-year-old male presented with generalized urticaria in September 2020. He had no past history of allergies, but had transient autoimmune thyroiditis in 2018, which subsequently resolved.

Initial complete blood count showed normal haemoglobin level and platelet count. However, his white blood cell (WBC) count was elevated at 19.2 x 109/L (normal range, 4.0–10.0 x 109/L). WBC differential showed normal levels of neutrophils and lymphocytes, with 60 percent eosinophils at 9.6 x 109/L (normal range, 0–0.7 x 109/L). His serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) level was also elevated at 1,456 IU/mL (normal levels, <100 IU/mL), but tryptase level was normal. Further laboratory workup revealed no obvious infections or abnormalities related to autoimmune markers, such as antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), rheumatoid factor (RF), complement components C3 and C4, and anti–double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. PET-CT scan showed cutaneous soft tissue swelling corresponding to sites of the urticaria. At presentation, the patient also had a few palpable lymph nodes (LNs). LN biopsy showed eosinophilic infiltration, possibly caused by eosinophilic lymphadenitis.

Bone marrow examination revealed eosinophilia, but no evidence of malignant cells. Cytogenetic evaluations were normal, while molecular tests were negative for KIT exon 17 mutation and gene fusions involving FIP1-like-1-platelet–derived growth factor receptor α (FIP1L1-PDGFRA), PDGFRβ (PDGFRB), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and BCR-ABL. Hence, the presence of myeloid malignancy, including myeloproliferative neoplasm or chronic eosinophilic leukaemia, was excluded. PET-CT scan did not show presence of lymphoma.

Further investigations examining end-organ damage, including lung function tests, nerve conduction studies, electrocardiography (ECG) and chest X-ray, all produced normal results. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) with skin involvement was made.

Treatment

In late September 2020, prednisolone 1 mg/kg was initiated, which resulted in immediate improvement in the urticarial rash. In January 2021, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 250 mg BID was started while simultaneously tapering off the steroid. Unfortunately, by the end of January, the patient had worsening of the skin rash, which necessitated escalation of the steroid dose. In March 2021, another attempt of steroid tapering resulted in increased eosinophil count and further worsening of the rash. While on steroid treatment, the patient had gained approximately 8 kg in body weight and developed Cushingoid facial features (moon face).

In July 2021, mepolizumab treatment was initiated as monthly 300 mg subcutaneous injections. After just two doses, the skin rash fully resolved (by week 5), and the patient was completely weaned off the corticosteroid by late August 2021 (by week 6).

The patient continued with self-administered monthly injections of mepolizumab and bi-monthly follow-ups. When last seen on 30 May 2024, he remained stable with normal eosinophil counts (0.06 x 109/L) and had no disease flares, apart from occasional urticaria (once or twice a month), which did not impact his quality of life (QoL). His swollen LNs and Cushingoid features had resolved, and his weight had returned to normal. The patient tolerated mepolizumab treatment well over the past 3 years and had not reported any drug-related adverse effects.

Case 2: Idiopathic HES patient with GI involvement refusing OCS

Presentation and investigations

A 31-year-old male with good past health presented with severe abdominal pain on 15 June 2022. At presentation, his haemoglobin and platelet levels were normal, but WBC count was elevated at 12 x 109/L, with an absolute eosinophil count of 1.3 x 109/L. CT scan showed enlarged abdominal LNs. The patient was given an analgesic for abdominal pain. However, a week later, his pain worsened with further abdominal distention and onset of diarrhoea. PET-CT scan showed ascites. On 8 July 2022, his WBC and eosinophil counts were 24 x 109/L and 12.8 x 109/L, respectively. Abdominal diagnostic paracentesis revealed a total cell count of 22,000/μL in the aspirated fluid with 98 percent eosinophils, suggestive of eosinophilic peritonitis. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy showed oesophagitis, duodenitis, ileitis, and colitis. Biopsies taken from these areas all showed eosinophilic infiltration consistent with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Screening for autoimmune markers (ie, ANAs, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCAs], RF, complement C3 and C4, and anti-dsDNA and anti-ENA antibodies) showed negative results. PET-CT scan revealed a few reactive abdominal LNs, but no obvious lymphoma. Bone marrow evaluation showed reactive eosinophilia with no abnormal cellular infiltration. Further assessments, including cytogenetics and gene fusion panels (using fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH] and next-generation sequencing [NGS]), were negative, which excluded chronic eosinophilic leukaemia and myeloproliferative neoplasm. Chest X-ray, lung function tests and ECG were normal, ruling out involvement of other organs.

Treatment

The patient refused corticosteroid treatment because of potential side effects. Therefore, first-line treatment with mepolizumab 300 mg monthly injections was initiated on 22 July 2022. His eosinophil count rapidly normalized to <0.5 x 109/L after the second dose of mepolizumab (week 5), and his symptoms also gradually started to improve. His stool consistency became normal after 6 weeks, and the abdominal distention completely resolved within 8 weeks. CT re-assessment in February 2023 showed resolution of all abdominal LNs and ascites.

This patient self-injects his monthly mepolizumab dose and is followed up every 3 months. Last seen on 6 June 2024, he remained asymptomatic without experiencing any side effects from mepolizumab use. His latest blood counts, including haemoglobin, platelet level, WBC, and eosinophil count (0.23 x 109/L) were normal.

Discussion

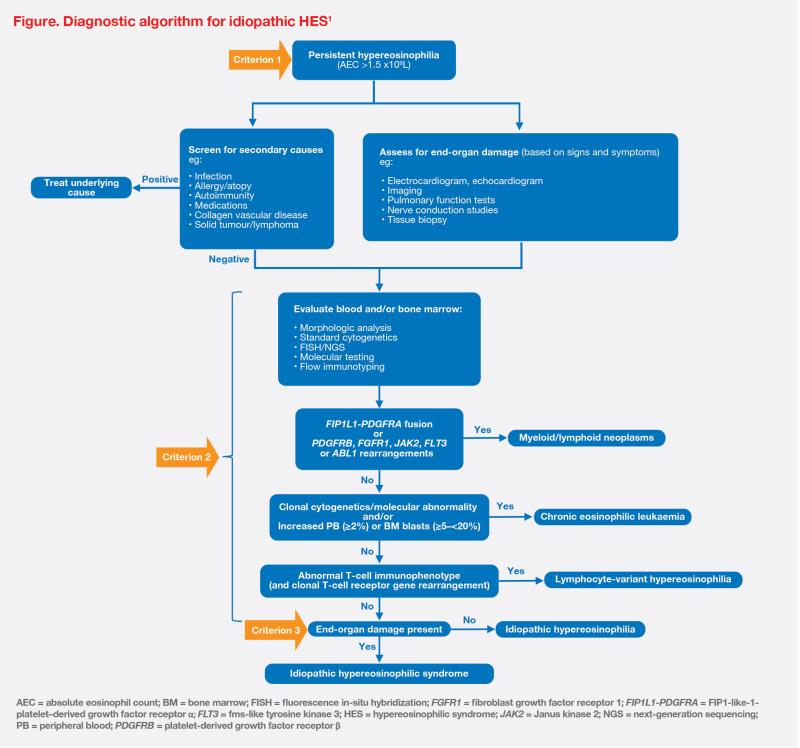

HES is a group of rare blood disorders characterized by persistently elevated blood eosinophil count and organ damage/dysfunction. A diagnosis of idiopathic HES requires three main criteria to be met: (1) persistent hypereosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count >1.5 x 109/L), (2) exclusion of all primary (clonal) and secondary (reactive) causes of eosinophilia, and (3) presence of eosinophil-mediated end-organ damage.1 (Figure)

When patients present with hypereosinophilia, it is important to determine clinical classification of the disease, which guides appropriate treatment that targets the underlying aetiology. The initial diagnostic workup should rule out reactive causes, such as autoimmune diseases (eg, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis [EGPA]), infections/infestations (eg, parasites), underlying allergies/ atopy (eg, chronic eczema, chronic asthma), underlying lymphoma (eg, T-cell and Hodgkin’s lymphoma), or certain medications. After exclusion of secondary causes of eosinophilia, the work-up should proceed to evaluation of blood and bone marrow for clonal causes including myeloid/ lymphoid neoplasms with gene fusions (eg, FIP1L1-PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, PCM1-JAK2, and BCR-ABL), chronic eosinophilic leukaemia, and lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia.1 (Figure)

In the primary care setting, family physicians can confidently exclude obvious reactive causes of hypereosinophilia. These include allergies, infections, and chronic atopic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and asthma.1 Based on our experience, allergic diseases and parasitic infections typically do not lead to severe eosinophilia (<5 x 109/L). However, if significant eosinophilia remains persistent for >6 months without obvious reactive causes, the patient should be referred to a specialist for further evaluation and treatment. Of note, any evidence of end-organ damage (eg, skin, gastrointestinal [GI] or respiratory manifestations, peripheral neuropathies, cardiac symptoms) should prompt earlier referral.

As observed in our two cases, skin and GI tract are the most common organ systems affected by HES. Other clinical manifestations can include eosinophilic vasculitis, peripheral neuropathy, and rare but potentially life-threatening pulmonary and cardiac involvement, such as myocarditis and valvular dysfunction.1

Investigations for organ damage depend on the patient’s specific symptoms. For example, endoscopy should be performed when a patient presents with GI symptoms. Further screening should also include radiological imaging of the chest (X-ray and/or high-resolution CT [HRCT] scan) and lung function test to rule out any pulmonary involvement, and ECG to exclude cardiac causes. If a patient has unusual skin lesions, a skin biopsy may be necessary. PET-CT scan is recommended for suspected secondary eosinophilia related to lymphoma, while LN biopsy is warranted for patients with enlarged LNs.

The main goals of HES treatment are to achieve sustained reductions in eosinophil counts, reverse and prevent further eosinophil-mediated end-organ damage, and improve and maintain patients’ QoL.2 Oral corticosteroids (OCS) are the first-line standard-of-care treatment for HES. OCS-sparing immunosuppressants, such as MMF, may be added to reduce complications associated with long-term exposure to OCS.1,3 Typically, patients who are on OCS for >3 months should be candidates for OCS-sparing drugs.

Mepolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets human interleukin-5 (IL-5), thereby inhibiting IL-5 signalling, and reducing the production and survival of eosinophils. It is indicated as an add-on treatment for adult patients with inadequately controlled HES without an identifiable nonhaematologic secondary cause.4

Our first patient case had HES that was steroid-dependent/steroid-refractory. Remarkably, after initiation of mepolizumab, the patient had rapid resolution of skin rash, and completely discontinued steroid treatment within 6 weeks. Mepolizumab was used in the first-line setting for our second case, as he refused treatment with OCS. Despite having severe eosinophilic gastroenteritis that involved the entire GI tract, the patient also had a rapid response to mepolizumab, achieving normal eosinophil counts and resolution of all symptoms within the first few weeks of treatment.

In a 32-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial (n=108), mepolizumab significantly reduced the occurrence of flares in patients with HES vs placebo (28 vs 56 percent; p=0.002). On-treatment adverse events occurred at similar rates in the two groups (89 vs 87 percent).2 Eligible patients from both arms of the trial entered an open-label extension (OLE) study (n=102), where all patients received mepolizumab for 20 weeks (final dose administered at week 16). Sustained reduction of flares was reported in 94 percent of patients who continued mepolizumab treatment. In addition, no new safety signals were reported.4,5

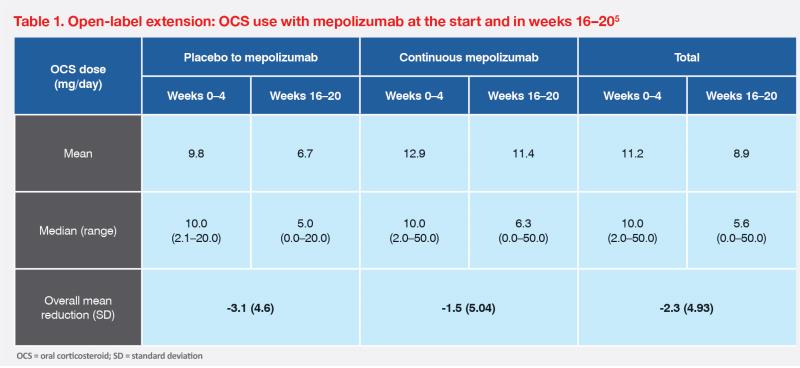

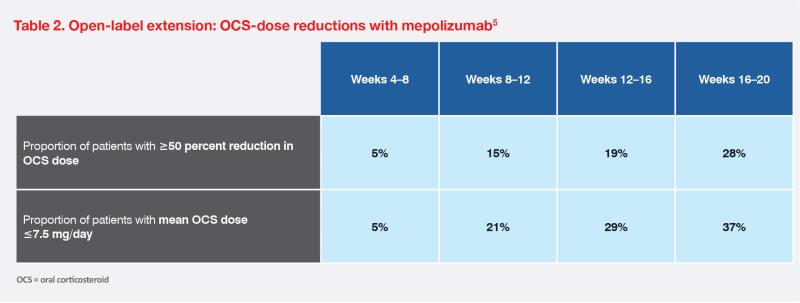

Reducing OCS dependence is a key goal of nonsteroidal HES therapies. As noted in our first case and the OLE study, mepolizumab was associated with rapid reduction in OCS dose; 28 percent of patients in the OLE study were able to reduce OCS use by ≥50 percent in weeks 16–20.5 (Tables 1 and 2)