First-line chemo-IO in a patient with advanced dMMR endometrial cancer

Presentation, treatment and response

A 52-year-old premenopausal lady presented in May 2023 with extremely heavy menstrual bleeding. She was a nonsmoker and nondrinker, with no known family history of cancer.

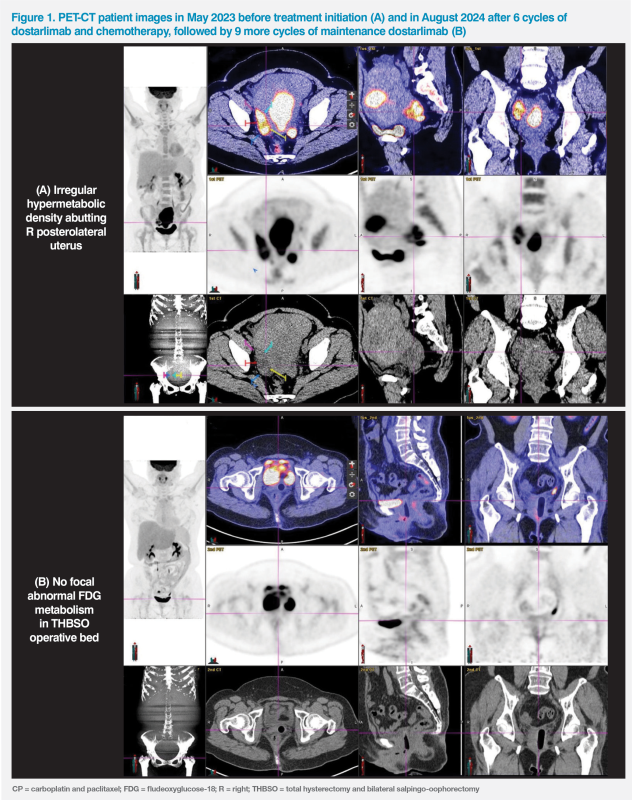

Endometrial aspiration biopsy revealed grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma. A subsequent PET-CT scan showed a large 13.5 x 6.5 cm hypermetabolic mass at endometrium with early myometrial invasion, compatible with uterine malignancy; extra-uterine 18F-FDG uptake in the posterolateral aspect of uterus and pelvic side wall, indicating metastatic disease; nonspecific uptake at abdominal lymph nodes (LNs) was noted. (Figure 1A)

The patient received total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with periaortic LN resection. Residual disease in the pouch of Douglas and myometrial involvement were suspected during the operation. Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 1.

Histology analysis showed no LN involvement. Immunohistochemistry indicated mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), loss of PAX2, and MLH1 promoter hypermethylation. In view of microscopic disease in the peritoneum, the patient was diagnosed with stage IVA endometrial cancer (EC).

After discussing the data from the RUBY trial, which were recently released at the time, the patient agreed to receive chemo-immunotherapy (IO) with dostarlimab (500 mg) plus carboplatin (area under the concentration–time curve, 5 mg/mL/min) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) (CP), every 3 weeks for six cycles, followed by maintenance dostarlimab (1,000 mg) every 6 weeks.1 She was also given a 25 fractions pelvic radiotherapy (RT) regimen for 5 weeks to enhance locoregional control.

She experienced grade 1 neuropathy while on chemotherapy and grade 1 diarrhoea after RT. A progress scan after completion of the last cycle of chemotherapy in August 2024 showed a clean tumour bed with no tumour recurrence. (Figure 1B)

Last seen in August 2024, 14 months after starting chemo-IO (ie, after a total of 15 cycles of dostarlimab, including nine maintenance doses), the patient continued to tolerate treatment very well and had no disease recurrence. After the first cycle of dostarlimab and chemotherapy in June 2023, she had a mild (grade 1) elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, which gradually resolved in February 2024 during her fourth cycle of dostarlimab maintenance (received Q6W). She also experienced some occasional mild pruritus, which did not require any treatment. She is expected to receive dostarlimab for a total of 3 years.

Discussion

Standard first-line chemotherapy with CP for primary advanced EC is associated with a median overall survival (OS) of <3 years, leaving a considerable unmet need for more efficacious treatment options. Use of IO was viewed as a promising strategy for dMMR tumours, like our patient’s, which account for 25–30 percent of ECs and are associated with an increased expression of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2), which makes them potentially susceptible to anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies.1

Dostarlimab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting the PD-1 receptor.1 It was initially approved as a monotherapy for dMMR/microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) advanced or recurrent EC that has progressed on or following prior treatment with a platinum-containing regimen on the basis of positive findings from the phase I, open-label, single-arm GARNET trial.2 Results of the phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled RUBY trial have subsequently led to the inclusion of dostarlimab plus CP as one of the category 1, preferred, first-line systemic therapy options for primary advanced or recurrent EC in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines.3

Of patients enrolled in the RUBY trial, 241 received dostarlimab plus CP and 246 received placebo plus CP. In the overall population, 24 percent of patients had dMMR/MSI-H tumours and a third had primary stage IV disease, like the patient described in the present case study. Investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) among dMMR/MSI-H patients was one of the primary endpoints, with the remaining two being PFS in the overall population and overall survival (OS) in the overall population.4

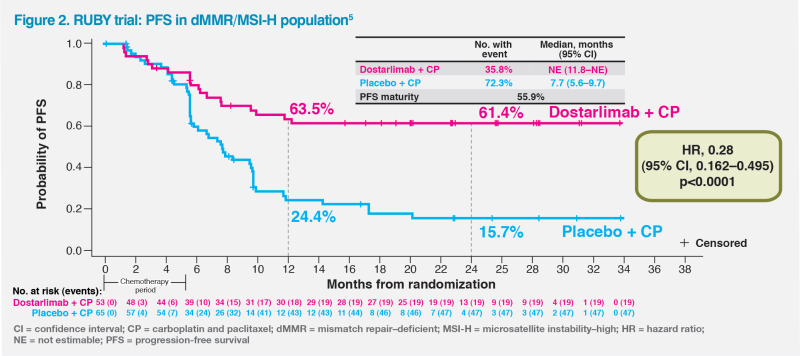

At a median follow-up of 24.8 months, dostarlimab plus CP was associated with a 72 percent lower risk of disease progression or death vs chemotherapy alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.28; 95 percent confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.50; p<0.001) among patients with dMMR/MSI-H tumours.1 The PFS probability curves for dostarlimab plus CP and CP alone began to clearly separate before 6 months, shortly after completion of the chemotherapy phase. At 12 months, PFS rate was 63.5 percent with dostarlimab plus CP vs 24.4 percent with CP alone in dMMR/ MSI-H patients. At 24 months, PFS rate in the dostarlimab plus CP group decreased by only 2.1 percent, compared with an 8.7 percent drop in the CP alone group (24-month PFS rate, 61.4 vs 15.7 percent).5 (Figure 2)

The PFS plateau observed in the dostarlimab plus CP group between 12 and 24 months is reflected in sustained treatment response through 24 months in these patients. The proportion of patients still in response at 24 months was 62.1 vs 13.2 percent in the dostarlimab plus CP vs CP alone group.1

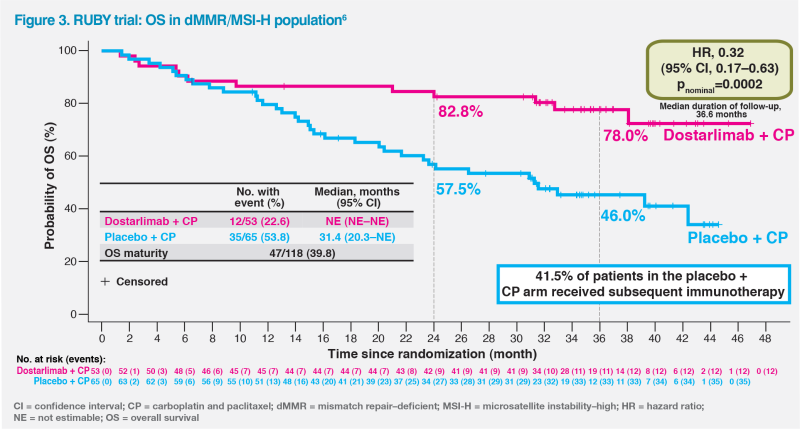

At a median follow-up of 36.6 months, dostarlimab plus CP demonstrated a substantial, unprecedented OS benefit in a prespecified analysis of patients with dMMR/MSI-H tumours, achieving an HR of 0.32 (95 percent CI, 0.17–0.63; pnominal=0.0002). Median OS was not estimable (NE) in the dostarlimab plus CP group vs 31.4 months in the CP alone group. More than three-quarters of patients (78.0 percent) in the dostarlimab plus CP group remained alive at 3 years compared with less than half (46.0 percent) in the CP alone group – a difference made all the more notable given that 41.5 percent of patients in the CP alone group received IO as the first subsequent anticancer therapy after progression.6 (Figure 3)

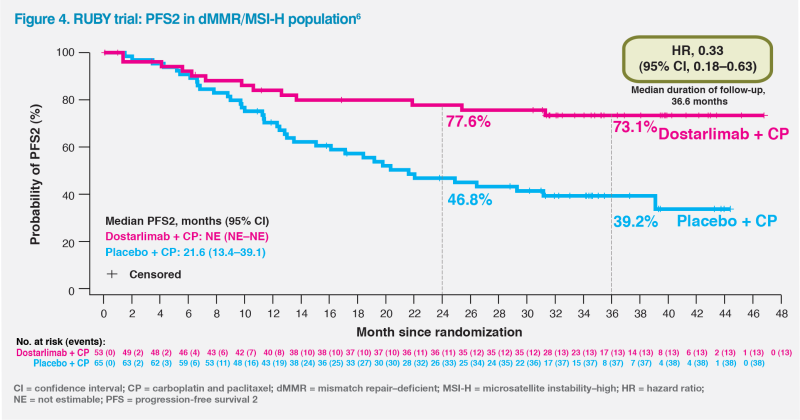

The observed OS benefit was further supported by improvement in PFS2, which depicts a clinical benefit beyond the first progression in patients receiving dostarlimab plus CP. Among patients with dMMR/MSI-H tumours, the 3-year PFS2 rates for dostarlimab plus CP vs CP alone were 73.1 vs 39.2 percent. The numerical improvement in PFS2 could not be calculated in this population at the second interim analysis as median PFS2 was not yet reached in the dostarlimab arm vs 21.6 months in the placebo arm. The HR of 0.33 (95 percent CI, 0.18–0.63) for PFS2 was consistent with the primary efficacy analyses of PFS and OS, demonstrating that dostarlimab’s benefits were sustained on the first subsequent anticancer therapy with delayed time to next progression or death.6 (Figure 4)

At a median duration of treatment of 43 weeks for dostarlimab plus CP and 36 weeks for CP alone, the rates of grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were 72.2 and 60.2 percent, respectively, while serious TEAEs occurred in 39.8 and 28.0 percent of patients, respectively. TEAEs led to discontinuation of dostarlimab in 19.1 percent of patients and to discontinuation of placebo in 8.1 percent of patients. TEAEs related to dostarlimab led to death in <1 percent of patients.6

Immune-related (IR) ALT level increase observed in our patient was reported in 5.8 percent of dostarlimab-treated patients in the RUBY trial (vs 0.8 percent in the placebo group). Other common IRAEs were hypothyroidism (11.2 percent with dostarlimab plus CP vs 2.8 percent with CP alone), rash (6.6 vs 2.0 percent), and arthralgia (5.8 vs 6.5 percent).1

In summary, intensification of standard systemic therapy with dostarlimab improves PFS, OS, and PFS2, while offering good tolerability in patients with primary advanced EC and dMMR/MSI-H tumours, whose disease is substantially more likely to recur with CP alone.