HIMALAYA trial showed that complete and partial responses are considerably more likely in patients with unresectable HCC treated with immunotherapy

vs the previous standard of care, sorafenib.

HIMALAYA trial showed that complete and partial responses are considerably more likely in patients with unresectable HCC treated with immunotherapy

vs the previous standard of care, sorafenib.History and presentation

A 55-year-old male was diagnosed with localized hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 2009. Over the next 10 years, he had multiple episodes of disease recurrence, which were managed with surgical resection and locoregional therapy such as ablation or transarterial chemoembolization.

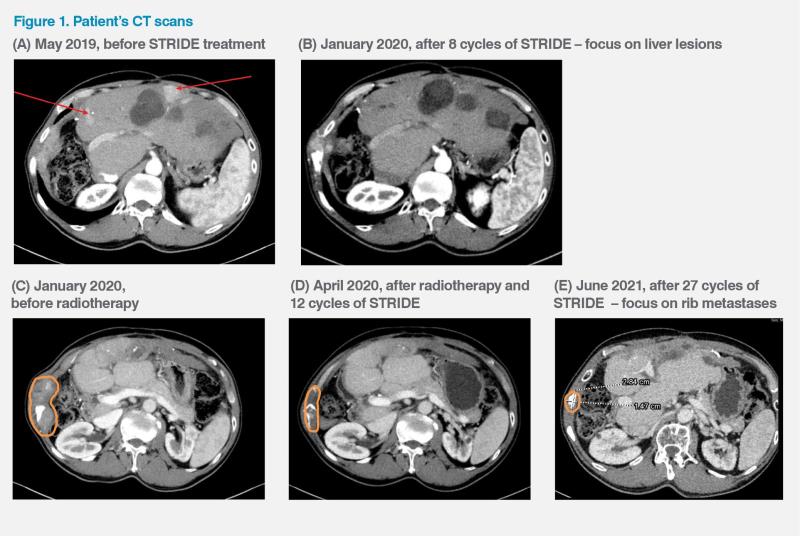

However, in May 2019, the patient developed multifocal HCC and metastasis in one of the right ribs, which caused considerable discomfort. (Figure 1A) His disease was classified as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C. He had normal liver function (Child-Pugh class A) and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 0. His serum alphafetoprotein (AFP) level was 111 ng/mL. There was no microvascular invasion or lymph node metastasis.

The patient had benign prostatic hyperplasia and a history of hypertension, which were well controlled with doxazosin and lisinopril, respectively. He was also a hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier and was on entecavir.

Treatment and response

Given the multifocality and metastatic nature of the disease, it was decided to initiate systemic treatment. In May 2019, the patient was put on the STRIDE (Single Tremelimumab Regular Interval Durvalumab) regimen: tremelimumab (300 mg, one priming dose) plus durvalumab (1,500 mg Q4W).

After eight treatment cycles, the patient developed a new palpable bone metastasis in the right rib, but the initial right rib bone metastasis showed response to STRIDE, and in January 2020, all the liver lesions complete resolution or significant shrinkage. (Figure 1B) The newly developed rib metastasis was subsequently treated with radiotherapy while the patient continued to receive durvalumab. Over the next several months, his rib lesions became smaller and the liver lesions remained treated. (Figure 1C–E) His disease eventually went into complete remission in October 2020. However, in March 2024, a new liver recurrence measuring 1.7 cm in the longest dimension was detected. He was given another round of radiotherapy for that lesion and is expected to continue with the STRIDE regimen indefinitely. As of May 2024, the patient had received a total of 59 treatment cycles with the last dose given in April 2024.

The patient tolerated the treatment well, apart from developing mild pruritus during the initial three cycles, which was managed with topical emollients, and hypothyroidism, which became apparent after eight treatment cycles and is treated with lifelong thyroxine replacement. His current ECOG PS is 0.

Discussion

According to the BCLC prognosis and treatment strategy (2022 update), the standard of care for advanced (stage C) HCC is atezolizumab plus bevacizumab or tremelimumab plus durvalumab. Durvalumab, sorafenib, or lenvatinib monotherapy can be an alternative firstline treatment if immunotherapy combination is not feasible.1

Combining agents that target different steps in the cancer immunity cycle is an effective strategy that can enhance the overall antitumour response. Tremelimumab, an anti–CTLA-4 antibody, contributes to T-cell activation, priming the immune response to cancer and fostering cancer cell death, whereas durvalumab, an anti–PD-L1 antibody, subsequently counters the tumour’s immune-evading tactics and releases the inhibition of immune responses at the tumour site.2,3

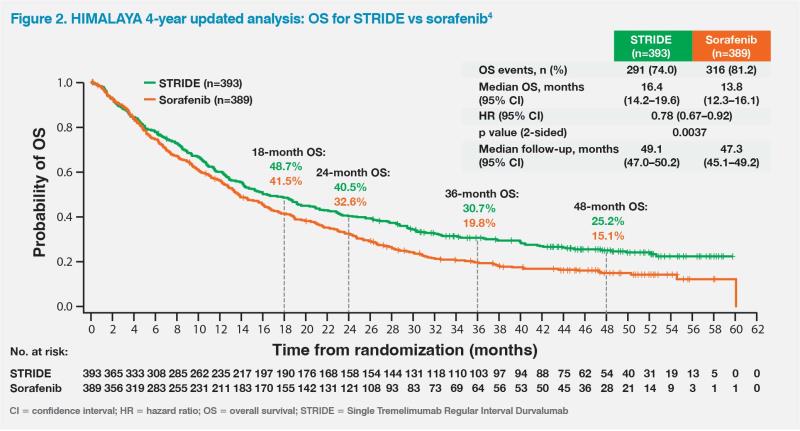

The patient’s ongoing 5-year survival while on the STRIDE regimen is consistent with results of the randomized, multicentre, phase III HIMALAYA trial, which compared STRIDE (n=393) with durvalumab monotherapy (n=389) and sorafenib (n=389) in patients with unresectable HCC and no previous systemic treatment.3,4 After a median follow-up of approximately 33 months, STRIDE significantly improved OS vs sorafenib (median, 16.4 vs 13.8 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.78; 96.02 percent confidence interval [CI], 0.65–0.93; p=0.0035), while durvalumab monotherapy was noninferior to sorafenib for OS.3

Remarkably, 25.2 percent of patients in the STRIDE arm were still alive at 4 years vs 15.1 percent with sorafenib, which was highlighted by the study’s authors as an unprecedented survival rate in this disease setting.4 (Figure 2)

While the Kaplan–Meier estimates for median progression-free survival were similar for STRIDE and sorafenib, 12.5 percent of patients receiving STRIDE remained progression-free at the final data cutoff vs 4.9 percent with sorafenib.3 In addition, 46.9 percent of patients in the STRIDE arm continued to receive treatment for at least one cycle after objective disease progression, which is reflective of the strategy employed in this case, as the patient continued to benefit from treatment even after developing a new bone metastasis and liver recurrence, suggesting that progression may not necessarily imply resistance to immunotherapy.3

The HIMALAYA trial also showed that complete and partial responses (PR) are considerably more likely in patients with unresectable HCC treated with immunotherapy vs the previous standard of care, sorafenib. The objective response rate (ORR) among long-term survivors (≥36 months beyond randomization) was 51.5 percent with STRIDE vs 53.2 percent with durvalumab vs 15.6 percent with sorafenib. In the STRIDE and durvalumab arms, complete response (CR) rates were 11.7 and 6.3 percent, respectively, while no patients achieved a CR with sorafenib. Respective PR rates were 39.8, 46.8, and 15.6 percent.4

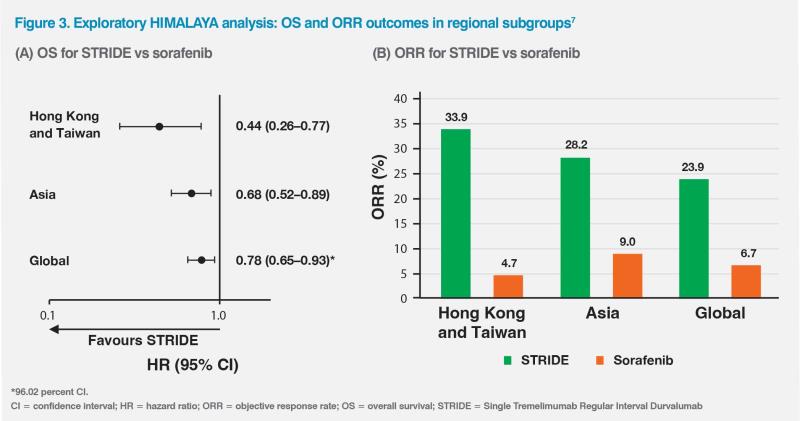

HCC aetiology varies globally and may affect response to immunotherapy.5,6 HBV is the main cause of HCC in most Asian countries, whereas hepatitis C virus or nonviral causes are more commonly associated with HCC in Japan and Western countries.5 An exploratory HIMALAYA analysis (n=479) evaluating the effectiveness of STRIDE vs sorafenib in patients from Asia, excluding Japan, showed a greater magnitude of OS benefit in the Asian subgroup (HR, 0.68; 95 percent CI, 0.52–0.89) vs the global population (HR, 0.78; 96.02 percent CI, 0.65–0.93). Within the Asian subgroup, STRIDE-treated patients from Hong Kong and Taiwan (n=141) were predominantly HBV carriers and had an even greater improvement in OS (HR, 0.44; 95 percent CI, 0.26–0.77). (Figure 3A) Of note, the ORRs among Hong Kong and Taiwan patients were 33.9 percent with STRIDE vs 4.7 percent with sorafenib, while the respective values in the Asian subgroup were 28.2 vs 9.0 percent and 23.9 vs 6.7 percent in the global population.7 (Figure 3B)

While on STRIDE, the patient developed mild pruritus and hypothyroidism, which were easily managed. In the HIMALAYA trial, these adverse events (AEs) occurred in 22.9 and 12.1 percent of patients receiving STRIDE, respectively.3 Other common any-grade AEs were diarrhoea (STRIDE: 26.5 percent, durvalumab: 14.9 percent, sorafenib: 44.7 percent), rash (22.4, 10.3, and 13.6 percent, respectively), decreased appetite (17.0, 13.7, and 17.9 percent, respectively), and fatigue (17.0, 9.8, and 19.0 percent, respectively). The updated HIMALAYA analysis did not identify new safety signals, indicating that long-term survival achieved with STRIDE or durvalumab was not associated with any substantial safety issues.4

The above case illustrates that the STRIDE regimen is effective and tolerable. Even patients who progress while on treatment may undergo locoregional therapy, if amenable, and continue to benefit from immunotherapy.