Viral respiratory infections often trigger asthma exacerbations. Patients with recent upper respiratory tract infection may experience worsened asthma control,” said Kwok. “In our [case-control] study, asthma patients who recently recovered from mild-to-moderate COVID-19 [within 30–270 days] were more likely to experience worse symptoms and uncontrolled disease than those who did not have COVID-19.” [Respir Res 2023;24:53]

“When asthma exacerbations occur, some patients may seek consultations in the private sector and receive steroids. This may lead to underreporting of exacerbations, making prevention more challenging,” he noted.

AHR is a hallmark of asthma involving bronchoconstriction in response to stimuli. While bronchoconstriction is primarily due to airway smooth muscle (ASM) contraction, AHR results from an interplay of ASM hypercontractility, airway inflammation, and airway remodelling (eg, fibrosis, smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and collagen deposition). [J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024;153:1181-1193; Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:16042]

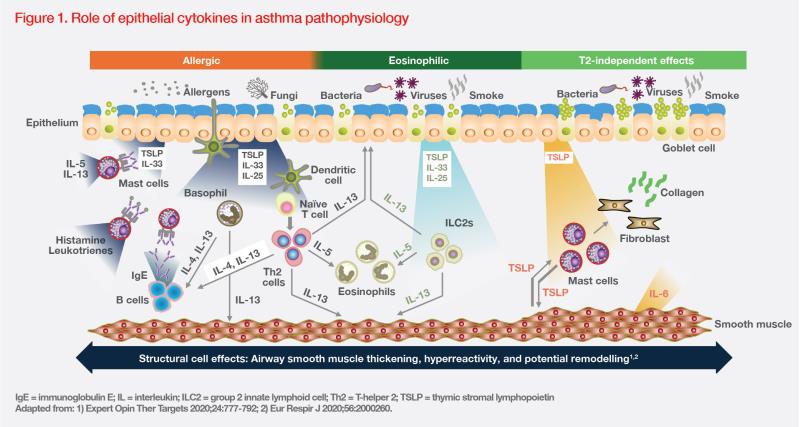

In response to triggers, the airway epithelium, which serves as an immune barrier to external environment, can contribute to remodelling through the release of various cytokines and growth factors acting on fibroblasts, airway glands, ASM, and the vasculature. Such structural changes further lead to airflow obstruction and enhance AHR. [J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024;153:1181-1193]

“Importantly, the severity of AHR impacts various clinical aspects of asthma, including disease severity, exacerbation risk, and the increased need for symptom control,” pointed out Kwok.

For patients with severe asthma despite high-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA), Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2024 guidelines recommend add-on treatment at Step 5, including biologics and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) depending on the inflammatory phenotype and other clinical features. [GINA guidelines 2024, https://ginasthma.org]

“While these medications are effective in general, asthma exacerbations still occur in some patients on GINA Step 5 treatment, including those on add-on biologics,” Kwok commented. [Chest 2020;157:790-804; Adv Ther 2023;40:2944-2964] “Furthermore, the use of inhaled medications can be challenging for some patients, especially those with limited respiratory flow.”

Difficult-to-treat T2-low asthma

T2-low asthma is recognized as a late-onset, difficult-to-treat endotype lacking T2-high markers. Currently, no validated biomarkers are available in clinical practice for this condition. [ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00309-2020; Biomedicines 2023;11:1226]

“At our centre, common assessments to identify patients with T2-low asthma include force expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], blood eosinophil counts [BEC] <150 cells/μL, immunoglobulin E [IgE] levels <100 IU/mL and fractional exhalednitric oxide [FeNO] <25 ppb,” Kwok noted. “During follow-up, it is crucial to monitor changes in these parameters.”

To date, treatment options for T2-low asthma have been limited. Patients with T2-low disease often show poor response to ICS and are ineligible for biologics such as anti-IgE and anti–interleukin (IL)-5. [

Eur Respir J 2021;57:2000528;

ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00309-2020] “In my experience, patients with T2-low disease receiving triple therapy with LABA, LAMA, and ICS often demonstrate a gradual decline in lung function in the initial years [as shown in the case reports]. Over the long term, further deterioration in lung function and potential adverse outcomes are expected,” Kwok said.

TSLP in asthma inflammation

TSLP is a key cytokine released by airway epithelial cells in response to environmental insults, such as allergens, viruses, and pollutants. Upon release, TSLP initiates a cascade of downstream inflammatory pathways, triggering diverse innate and adaptive immune responses. (Figure 1) [

Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792]

For instance, TSLP may synergize with other epithelial cytokines (eg, IL-25 or IL-33), inducing group 2 innate lymphoid cells to produce T2 cytokines (eg, IL-5, IL-13), which leads to eosinophilic inflammation. TSLP-activated dendritic cells may also induce T-cell differentiation and cytokine release, resulting in mucus hypersecretion in airway tissue and smooth muscle contraction in AHR. Additionally, TSLP may contribute to airway remodelling in different asthma inflammation endotypes through T2-independent effects involving smooth muscle cells, mast cells, and lung fibroblasts. (Figure 1) [Expert Opin Ther Targets 2020;24:777-792; Respir Res 2020;21:268]

“Targeting upstream mediators such as TSLP may inhibit the production of different inflammatory cytokines from different cell types, providing broader effects on airway inflammation and more effective asthma control, including in patients with T2-low disease,” Kwok pointed out. [Respir Res 2020;21:268; Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;208:13-24]

Tezepelumab improves asthma exacerbations and AHR

Tezepelumab is an IgG2λ monoclonal antibody targeting TSLP, which prevents its interactions with TSLP receptor. In Hong Kong, tezepelumab is indicated as an add-on maintenance treatment in adults and adolescents aged ≥12 years with inadequately controlled severe asthma despite maintenance treatment consisting of high-dose ICS. The recommended dosage of tezepelumab is 210 mg Q4W by subcutaneous injection. [Tezspire Hong Kong Prescribing Information]

Exacerbation reduction

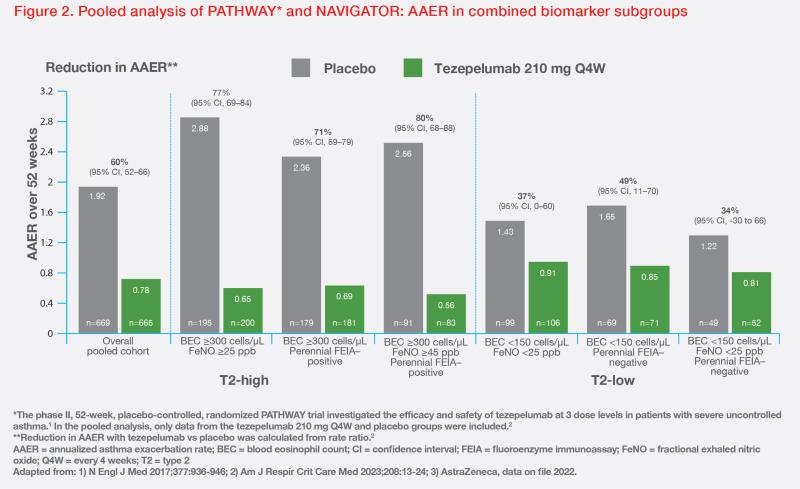

Tezepelumab was shown to reduce annualized asthma exacerbation rates (AAER) in patients with severe asthma despite treatment containing inhaled glucocorticoids in the phase II ATHWAY and phase III NAVIGATOR trials. [N Engl J Med 2017;377:936-946; N Engl J Med 2021;384:1800-1809]

In a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from PATHWAY and NAVIGATOR, tezepelumab demonstrated clinically meaningful reductions in AAER vs placebo. AAER reduction at 52 weeks was 60 percent (95 percent confidence interval [CI], 52–66) in the overall pooled cohort, and 80 percent (95 percent CI, 68–88 percent) in patients with BEC ≥300 cells/μL, FeNO ≥45 ppb and perennial allergy. Among T2-low patients, tezepelumab reduced AAER by 37 percent (95 percent CI, 0–60) vs placebo in those with BEC <150 cells/μL and FeNO <25 ppb, and by 34 percent (95 percent CI, -30 to 66) in those with BEC <150 cells/μL and FeNO <25 ppb without perennial allergy. (Figure 2) [

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;208:13-24; AstraZeneca, data on file 2022]

“Based on the findings from pooled analysis of PATHWAY and NAVIGATOR, tezepelumab can be effective [in preventing exacerbations] for severe asthma patients across various phenotypes, including T2-high and T2-low disease,” Kwok commented.

AHR improvements

Improvements in clinical outcomes observed with tezepelumab may be related, at least in part, to reductions in eosinophilic airway inflammation and AHR. [Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1299-1312] “Tezepelumab’s effect on eosinophilic inflammation may explain its pronounced benefits in patients with T2-high asthma. Meanwhile, improved AHR reflects better airway condition,” noted Kwok.

In the phase II CASCADE trial involving 99 patients with uncontrolled, moderate-to-severe asthma who completed ≥20 weeks of treatment and had bronchoscopy biopsy samples at both baseline and within 8 weeks after the last treatment, tezepelumab (n=48) demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in airway submucosal eosinophils vs placebo (n=51) (ratio of geometric least-squares means [LSM], 0.15; pnominal<0.0010). The greater reductions in eosinophils with tezepelumab vs placebo were observed across all baseline subgroups, including BEC. In exploratory analysis, tezepelumab demonstrated significantly greater reduction in AHR to mannitol vs placebo (LSM change from baseline in interpolated or extrapolated provoking dose of mannitol required to induce ≥15 percent reduction in FEV1 [PD15], 197.4 vs 58.6 mg; difference, 138.8; pnominal=0.030). [Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1299-1312]

A prespecified analysis of CASCADE showed that tezepelumab was associated with reduction in occlusive mucus plugs among 82 patients who completed ≥20 weeks of treatment and had CT scans at both baseline and a visit within 8 weeks after the last treatment. Mucus plug scores on CT scan were lower among patients in the tezepelumab vs placebo group (absolute mean change from baseline, -1.7 vs 0.0). More patients in the tezepelumab vs placebo group transitioned from having ≥1 mucus plug to having none (37.8 vs 13.3 percent). [NEJM Evid 2023;doi:10.1056/EVIDoa2300135]

In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled UPSTREAM trial involving 40 patients with uncontrolled asthma despite ICS treatment, blocking TSLP signalling with tezepelumab reduced the proportion of asthma patients with AHR. The mean change in PD15 expressed as doubling doses was 1.9 with tezepelumab vs 1.0 with placebo (p=0.06) from baseline to week 12. At week 12, 45 vs 16 percent of patients achieved a negative PD15 test (p=0.04). [Eur Respir J 2022;59:2101296]

Safety

“Tezepelumab is generally well tolerated, demonstrating an acceptable safety profile among patients with severe uncontrolled asthma in clinical trials,” commented Kwok. [Drugs Ther Perspect 2023;39:393-403]

In pooled analysis of PATHWAY and NAVIGATOR, the incidence of adverse events (AEs) was similar between the two groups. The most common AEs included nasopharyngitis (19.5 percent for tezepelumab vs 19.1 percent for placebo), upper respiratory tract infection (9.3 vs 13.3 percent), and arthralgia (3.8 vs 2.4 percent). Rates of injection-site reactions were 4 percent with tezepelumab vs 3 percent with placebo. [Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;208:13-24]

Summary & final thoughts

In asthma, TSLP contributes to AHR and remodelling through both eosinophilic inflammation and T2-independent effects involving smooth muscle cells, mast cells, and lung fibroblasts, making it an attractive therapeutic target. Clinical evidence has shown that blocking TSLP, which acts as an upstream regulator of multiple molecular pathways in asthma pathophysiology, with tezepelumab reduces asthma exacerbations and may improve AHR.

“Tezepelumab should be considered for severe asthma patients regardless of endotype, including those with T2-low disease,” Kwok concluded. “Further research is needed to optimize the classification and management of T2-low disease.”