Lifestyle interventions, including increased fibre intake, have been shown to be effective in management of metabolic diseases. At a meeting coordinated by the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP), Dr Elaine Chow of the Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, described different types of dietary fibre and their various benefits, and shared clinical evidence on the role of psyllium fibre in minimizing cardiometabolic risk factors, such as elevated LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), blood glucose levels and obesity.

How bad is Hong Kong’s “fibre gap”?

Dietary fibre, which ensures regular laxation, is a central component of a healthy diet. A large body of observational evidence indicates that a higher fibre intake is associated with reduced chronic disease risk and longer life. In dose-response meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies, additional 7–10 g of fibre on top of adequate fibre intake per day was associated with a 9 percent reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD), a 9 percent reduction in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a 10 percent reduction in colorectal cancer, and an 11 percent reduction in all-cause mortality. [Nutrients 2018;10:599]

Hong Kong’s Centre for Health Protection (CHP) recommends a dietary fibre intake of ≥25 g/day in adults and teenagers. [https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/90018.html] The difference between recommended and actual fibre intake is known as the “fibre gap”. A survey conducted in 2020–2022 in Hong Kong revealed that 97.9 percent of respondents aged ≥15 years consumed an average of <5 servings of fruit and vegetables per day, while a national survey in China showed an overall mean dietary fibre intake in adults of 9.7 g/day in 2015. [https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_1_report_eng_rectified.pdf; Nutr Rev 2020;78:43-53] “This intake is very low and very concerning,” remarked Chow.

Different fibres – different benefits

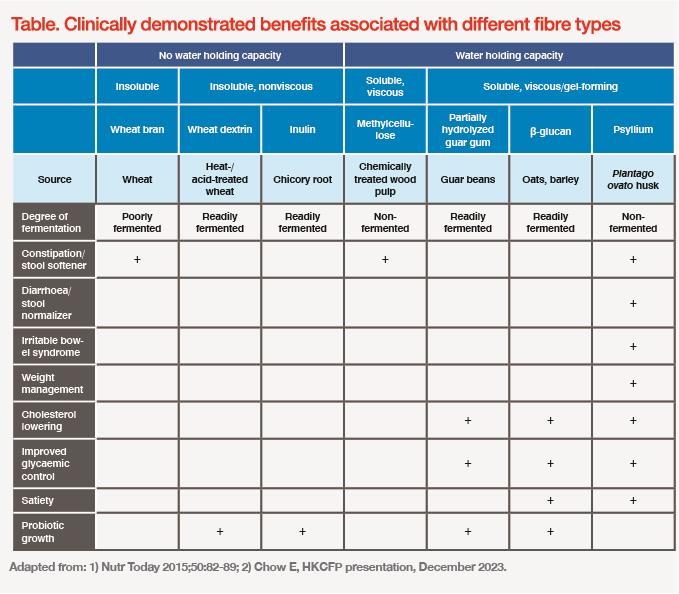

Although all dietary fibre contributes towards the recommended daily intake, different fibre types provide different health benefits, depending on their physicochemical properties and physiological effects. There are four main fibre characteristics that drive clinical efficacy: solubility, degree/rate of fermentation, viscosity, and gel formation. [Nutr Today 2015;50:82-89]

“For instance, wheat bran, which is a poorly fermented insoluble fibre, mainly helps with constipation but does not provide any cardiometabolic benefits. β-glucan, which is a soluble, viscous, gel-forming fibre, helps reduce cholesterol and glucose, but does not offer gastrointestinal [GI] benefits,” explained Chow. “Psyllium husk contains another type of [nonfermented, soluble, viscous, gel-forming] fibre, which is both a stool normalizer and helpful in cholesterol and glycaemic control.” (Table)

Natural properties define psyllium’s mode of action

Psyllium fibre comes from the Plantago ovato plant, is 100 percent natural and contains high levels (70–80 percent) of viscous soluble fibre.

Psyllium fibre softens and lubricates stools, but its health benefits extend beyond laxation. Its gel-forming properties lead to cholesterol and sugar trapping, thus minimizing their absorption in the small intestine. In addition, psyllium fibre increases chyme viscosity in a dose-dependent manner, thereby decreasing the interaction between food and digestive enzymes, ultimately leading to lower blood cholesterol and glucose levels. [J Acad Nutr Diet 2017;117:251-264]

As chyme viscosity is increased by psyllium fibre, cholesterol and sugars are absorbed further down the GI tract, in the distal ileum, where they stimulate mucosal L-cells to release glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) into the bloodstream. This in turn decreases appetite, increases pancreatic β-cell growth, enhances insulin production and sensitivity, and decreases secretion of glucagon (a peptide that stimulates glucose production in the liver), leading to improved postprandial glucose homeostasis.

An additional mechanism by which psyllium fibre helps lower cholesterol is by reducing reabsorption of bile acids in the small intestine. As psyllium fibre gel traps bile acids in the intestine, more of them are eliminated in the waste. As a result, the liver utilizes more serum cholesterol to produce bile. [Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59:1055-1059; J Lipid Res 1992;33:1183-1192]

Psyllium’s cholesterol-, glucose- and weight-lowering effects

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel, multicentre trial evaluated long-term effectiveness of psyllium fibre as an adjunct to diet in treatment of primary hypercholesterolaemia. After following American Heart Association’s Step I diet for 8 weeks, eligible subjects with serum LDL-C concentrations of 3.36–4.91 mmol/L were randomized to receive psyllium fibre 5.1 g (n=197; average BMI, 25.5 kg/m2) or a cellulose placebo (n=51; average BMI, 25.8 kg/m2) twice daily for 26 weeks, while continuing diet therapy. After 6 months of treatment, serum total cholesterol and LDL-C concentrations were 4.7 percent and 6.7 percent lower, respectively, in the psyllium fibre vs placebo group (p<0.001 for both). [Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:1433-1438]

In a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCT) involving 1,924 individuals with or without hypercholesterolaemia, psyllium at a median dose of 10.2 g was shown to significantly reduce levels of LDL-C (mean difference [MD] from baseline [BL], -0.33 mmol/L; p<0.00001), non–HDL-cholesterol (MD, -0.39 mmol/L; p<0.00001), and apolipoprotein B (MD, -0.05 g/L; p<0.0001). [Am J Clin Nutr 2018;108:922-932]

“While psyllium fibre can significantly reduce cholesterol levels when used on its own or in combination with dietary intervention, these changes may not be sufficient for individuals at higher CVD risk, whose LDL-C targets are lower. Yet, psyllium fibre could still be of help in these cases, as it enhances cholesterol-lowering efficacy of statins,” said Chow.

A meta-analysis of three RCTs assessing statins’ efficacy when used with or without psyllium for 4–12 weeks showed a clinically and statistically significant cholesterol-lowering advantage for psyllium plus statin combination vs statin monotherapy. “In this meta-analysis, taking psyllium before meals led to LDL-C reduction equivalent to doubling the statin dose,” noted Chow. [Am J Cardiol 2018;122:1169-1174]

In a RCT conducted in patients with T2DM (mean BL weight, 89 kg; mean BL BMI, 31.7 kg/m2), 8 weeks of psyllium fibre 10.5 g daily supplementation (n=18) led to significant reductions in weight (MD, -3.6 kg vs -0.8 kg; p<0.001), BMI (MD, -0.9 kg/m2 vs +0.3 kg/m2; p<0.001), waist circumference (MD, -2.7 cm vs -0.4 cm; p<0.001), hip circumference (MD, -2.6 cm vs +0.5 cm; p<0.001), fasting blood sugar (MD, -43 mg/dL vs -5 mg/dL; p<0.001), HbA1c (MD, -1.0 percent vs 0.0 percent; p<0.001), insulin (MD, -8.2 μIU/mL vs +3.1 μIU/mL; p<0.001), C-peptide (MD, -2.0 ng/mL vs +0.9 ng/mL; p<0.001), and Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR; MD, -5.5 vs +0.8; p<0.001) vs the control group (n=18). [Nutr J 2016;15:86]

“These findings are corroborated by a meta-analysis of six RCTs [n=354], which showed that psyllium fibre, taken just before meals [mean dose, 10.8 g/day; mean duration, 4.8 months], was effective at decreasing body weight [MD, -2.1 kg; p<0.001], BMI [MD, -0.8 kg/m2; p<0.001] and waist circumference [MD, -2.2 cm; p<0.001] in overweight and obese individuals,” concluded Chow. [J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2023;35:468-447]