Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) is a progressive, fatal condition that predominantly affects older adults. The prognosis is poor, with a median overall survival (OS) of 3–5 years. The condition is often underrecognized or misdiagnosed due to low disease awareness and fragmented knowledge among healthcare professionals across specialties. This article provides practical advice for early diagnosis and treatment, with a focus on 5-year OS data from the ATTR-ACT trial of tafamidis and key recommendations from the 2023 American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines.

ATTR-CM: Not such a rare disease

ATTR-CM is defined by accumulation of transthyretin (TTR) fibrils in the heart and other organs, leading to cardiac and extracardiac symptoms. There are two genotypes of ATTR-CM: Wild-type and variant (hereditary), which are associated with ageing and TTR mutations, respectively. [Glob Heart 2023;18:59]

Once considered a rare disease, ATTR-CM is now known to be more prevalent than previously thought. Of note, it is an increasingly recognized cause of heart failure (HF), and is present in up to 15 percent of patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). [Glob Heart 2023;18:59; J Am Heart Assoc 2023;12:e029705]

Multidisciplinary approach to early diagnosis

Early diagnosis is critical for improving OS and/or preventing loss of organ function in patients with ATTR-CM. However, diagnostic delay and misdiagnosis are recognized problems in ATTR-CM. A considerable proportion of patients (wild-type, 11 percent; variant, 23 percent) have to consult ≥5 physicians before receiving a correct diagnosis. [Front Cardiovasc Med 2023:10:1154594; Heart Fail Rev 2022;27:785-793; Cardiol Ther 2021;10:141-159]

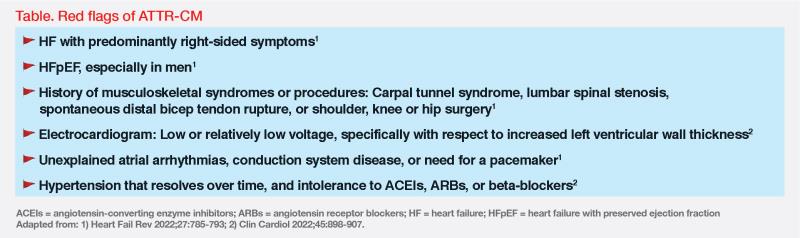

Recognizing potential red flags is key to early detection of ATTR-CM. (Table) Musculoskeletal symptoms often precede cardiac or neurologic manifestations by several years, which highlights the need for awareness among orthopaedists as well as neurologists and cardiologists. Cardiac manifestations often present as restrictive cardiomyopathy and can progress to conduction system disease, aortic stenosis, and eventually, HF. Awareness and recognition of the constellation of cardiac and extracardiac symptoms among various healthcare specialists would help with early diagnosis of ATTR-CM. [Heart Fail Rev 2022;27:785-793; Clin Cardiol 2022;45:898-907; Eur Heart J 2022;43:2633-2635]

Noninvasive diagnostic approach available

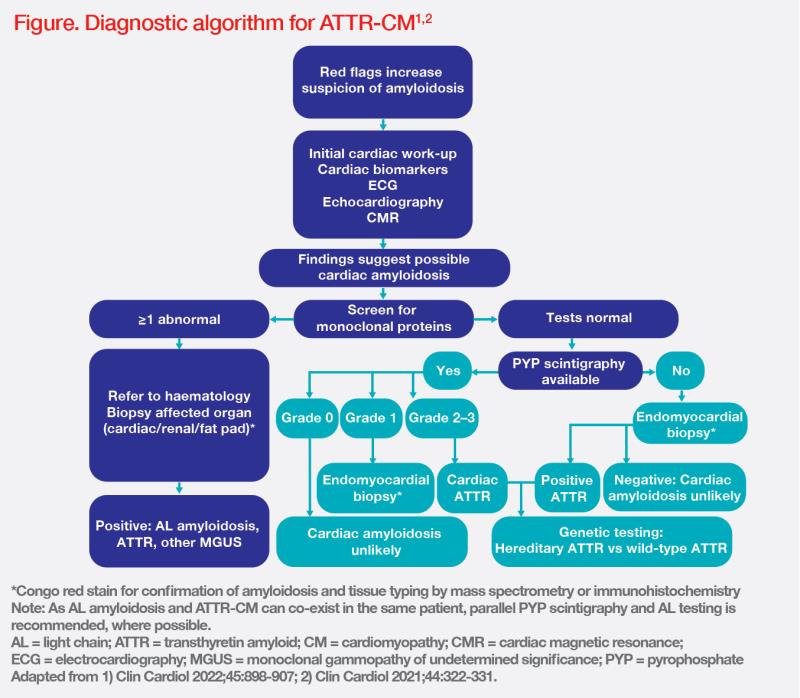

The emergence of newer noninvasive imaging techniques potentially obviates the need for invasive endomyocardial biopsy. An initial cardiac workup should be provided in suspected cases. Clues to diagnosis include low or relatively low voltage on electrocardiogram (ECG), especially alongside increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness. Echocardiography enables identification of cardiac red flags, such as aortic stenosis and HFpEF. If results from echocardiography are unclear, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) can provide detailed assessment of cardiac structure, including identification of LV hypertrophy, function, and tissue characteristics. Elevated levels of serum N‐terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponins are useful cardiac indicators of disease burden. (Figure) [Clin Cardiol 2022;45:898- 907]

Patients with normal monoclonal protein test results should undergo invasive pyrophosphate (PYP) scintigraphy. Grade 2/3 cardiac uptake on the scan confirms ATTR-CM with high diagnostic accuracy. Once ATTR-CM is confirmed, genetic testing must be performed to differentiate wild-type from variant subtype disease. (Figure)

Tafamidis for all subtypes of ATTR-CM

Until 2019, no pharmacotherapies were approved for ATTR-CM. Tafamidis, a selective stabilizer of TTR, is the first US FDA–approved treatment for ATTR-CM and is indicated in both wildtype and variant subtypes. It works by preventing tetramer dissociation into monomers, which is the rate-limiting step in the amyloidogenic process. [Ann Pharmacother 2021;55:1502-1514; Tafamidis Prescribing Information, April 2023]

The US FDA approval was based on results of the phase III pivotal ATTR-ACT trial in patients with ATTR-CM (n=441), which showed reductions in both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular (CV)-related hospitalizations with tafamidis vs placebo. [Tafamidis Prescribing Information, April 2023; N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007-1016]

Early treatment improves long-term OS

Patients who completed ATTR-ACT were eligible for enrolment in an open-label, long-term extension study, in which patients who initially received tafamidis continued tafamidis meglumine 80 or 20 mg (n=176) while placebo recipients started tafamidis meglumine 80 or 20 mg (placebo-to-tafamidis group; n=177) for up to 60 months. Following a protocol amendment, all patients transitioned to treatment with tafamidis free acid 61 mg (bioequivalent to tafamidis meglumine 80 mg). [Circ Heart Fail 2022;15:e008193]

After a median follow-up of approximately 58 months, early initiation of tafamidis was found to significantly reduce the risk of death vs late initiation (median OS, 67.0 vs 35.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.59; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.44–0.79; p<0.001), highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment in ATTR-CM.

Of note, the placebo-to-tafamidis group still appeared to show a reduction in mortality vs the extrapolated placebo group after approximately 44 months of follow-up. Additionally, long-term OS benefit remained consistent in different subgroups without significant interaction, including baseline New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification (p=0.73) and genotype (wild-type or variant; p=0.58), suggesting that tafamidis may provide an OS benefit even in patients with more advanced disease and that all patients with ATTR-CM could benefit from treatment with tafamidis.

Tafamidis’ safety profile is comparable with placebo, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) being of mild or moderate in severity. Permanent treatment discontinuation occurred more frequently with placebo vs tafamidis (28.8 vs 21.2 percent) in ATTR-ACT. No new safety concerns emerged in the 5-year long-term extension study. [N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007-1016; Circ Heart Fail 2022;15:e008193]

Guideline recommendations

In the 2023 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Care for the Patient with Cardiac Amyloidosis, tafamidis is the only recommended medication for both wildtype and variant ATTR-CM. Although there are alternatives to tafamidis, they lack a similar evidence base and are not as well tolerated. [J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1076-1126]