Use of a C5 inhibitor in a patient with AOSD complicated by atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Presentation, investigation and treatment

A 42-year-old male was hospitalized with a 2-week history of persistent fever, generalized maculopapular rash, and right cervical lymphadenopathy. His medical history and family history were unremarkable.

During the first 2–3 weeks of hospitalization, infection was suspected. However, the patient continued to have persistent fever despite escalating antibiotics. Bone marrow examination showed active marrow with histiocytic proliferation, while results of cervical lymph node fine needle aspiration excluded lymphoma. Autoimmune screening and microbiological tests, including HIV test, were unremarkable except for a markedly elevated ferritin level, which peaked at 110,000 pmol/L. Taking into account his symptoms and test results, a diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) was made, and intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone was started.

On day 20, the patient developed acute encephalopathy and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 4 x 109/L), and was admitted to the intensive care unit. Both CT of the brain (CTB) and lumbar puncture showed unremarkable results. International normalized ratio was normal, which excluded disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) was suspected. While awaiting ADAMTS13 test results to confirm the diagnosis, three cycles of plasma exchange (PE) were started upon referral to our nephrology team. After 1 week, ADAMTS13 testing report showed normal results, which ruled out TTP.

Haematologists suspected immune thrombocytopenia on day 27, resulting in a switch from PE to IV immunoglobulin. Despite resolution of fever and improvement in ferritin level to 4,700 pmol/L, the patient’s platelet counts improved only slightly to 30–50 x 109/L. On day 29, the patient developed progressive kidney failure with a high creatinine level of 871 μmol/L, which required acute dialysis.

Macrophage activation syndrome/ haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (MAS/HLH), a serious complication of AOSD, was suspected due to an elevated CXCL9 level of 1,120 pg/mL and impaired natural killer cell function. Anti–interleukin (IL)-1 and dexamethasone were started upon rheumatology and haematology review, but anti–IL-1 was later stopped due to fungaemia. The patient’s condition deteriorated, showing acute seizure, while his platelet count dropped to 4 x 109/L again, ferritin level elevated to 220,000 pmol/L, and CXCL9 level increased to 6,849.0 pg/mL, which prompted reconsultation with haematologists.

On day 46, haematologists suspected atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS) triggered by MAS/ HLH flare and restarted PE while awaiting funding for eculizumab. The patient also underwent genetic testing for main aHUS genes, multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (MLPA) for structural variants within the CFH-CFHR gene region, and anti–complement factor H (CFH) antibody testing. Rheumatologists also reviewed the patient’s condition and initiated tocilizumab, which led to a notable clinical improvement.

Two doses of eculizumab were eventually given on days 71 and 78, followed by tocilizumab maintenance for his AOSD after the patient’s condition stabilized. The patient’s kidney function gradually improved after treatment and no longer required dialysis. On day 116, he was discharged to a convalescent hospital, with salient results including normalized platelet count of 186 x 109/L, creatine level of 73 μmol/L, and ferritin level of 5,368 pmol/L.

Genetic testing revealed negative results and no CFHR3-CFHR1 deletion. Anti-CFH testing showed a high level of CFH antibodies of 1,242 AU/mL, but we could not conduct post-treatment testing as the patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

aHUS is a rare, complement-mediated, severe form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) that manifests as acute kidney injury (AKI), thrombocytopenia, and microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. As illustrated in this case, diagnosis of aHUS can be challenging given its nonspecific and overlapping symptoms with other conditions such as TTP.1,2

The prognosis of aHUS patients is poor, as up to 40 percent of patients develop end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) or die during the first clinical manifestation, highlighting the urgency of early diagnosis and anti-complement treatment.2,3 Early referral to specialists should be considered in patients presenting with TMA symptoms such as fever, thrombocytopenia, and neurological symptoms (eg, confusion, seizure).

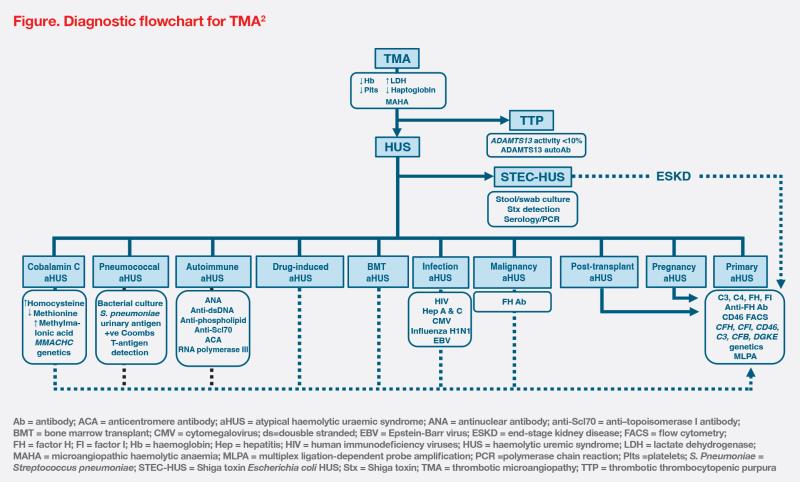

According to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) experts, TMA investigations should focus on determining the underlying aetiology and excluding other diagnoses. (Figure) Measurement of ADAMTS13 activity to diagnose or exclude TTP is of utmost urgency.2 Diagnosis of aHUS should be considered in the presence of thrombocytopenia and AKI, especially when ADAMTS13 test results are normal.1 Our hospital did not have the ADAMTS13 test few years ago during this case presentation, resulting in a brief delay in diagnosis. However, recent inclusion of the test in our hospital should expedite the diagnostic process.

Primary aHUS arises from genetic abnormalities, while secondary forms are attributed to a variety of conditions.2 (Figure) In our patient’s case, severe inflammation from AOSD or MAS/HLH may trigger aHUS, but the presence of anti-CFH antibodies may suggest an overlap between primary and secondary aHUS.1

Of note, delays in obtaining genetic test results should not prevent clinical diagnosis or lead to treatment postponement, as early complement treatment is crucial to preserve kidney function and avoid irreversible sequelae.2 As illustrated in our case, C5 inhibitor treatment with eculizumab was initiated ahead of genetic results, which allowed the patient to discontinue dialysis once his kidney function and platelet count normalized and his overall inflammation profile improved. These improvements were consistent with results of eculizumab’s two phase II clinical trials, which showed dialysis discontinuation in four of five patients, as well as significantly greater improvement in kidney function associated with earlier eculizumab treatment.3

Although the optimal duration of eculizumab treatment has not been determined, lifelong treatment is recommended due to the high risk of relapse (29.6 percent) and further kidney injury.4,5 Patients who stop eculizumab therapy should undergo regular and careful monitoring for relapse, especially in primary aHUS cases. Ravulizumab, another C5 inhibitor, could be an alternative maintenance treatment with less frequent dosing.5,6